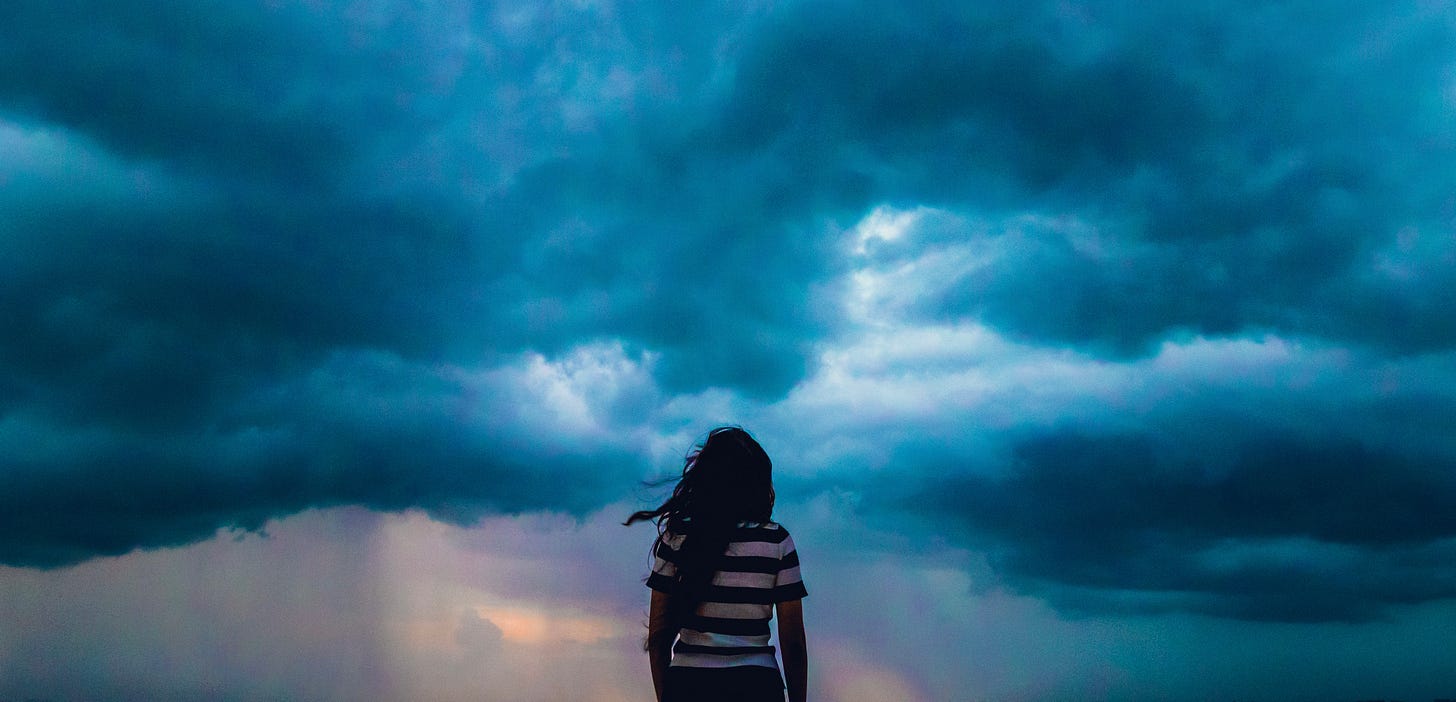

#4. Living Joyfully While Struggling in a Shitstorm

Is such a thing even possible? Desmond Tutu Thought So.

The world has mourned three icons of spirituality and global activism in less than three months.

First, Archbishop Desmond Tutu died on the day after Christmas at age 90.

On January 15 we honored the birth of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who would have been 93.

A week later, we lost the renowned Zen master and lifelong peace activist Thích Nhất Hạnh, 95, the father of mindfulness and engaged Buddhism.

These three men were friends as well as contemporaries; all were heroes of human social progress in the 20th century. In recognition of this, Thích Nhất Hạnh was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize; Rev. King and Archbishop Tutu were both awarded that singular honor.

But for some reason it is the Archbishop — freedom fighter, spiritual healer, and passionate advocate of universal human rights, for everyone from Palestinians to LGBTQ — whom I haven’t been able to get out of my mind.

As BBC South Africa correspondent @nomsa_maseko put it in her moving, three-minute tribute to Tutu:

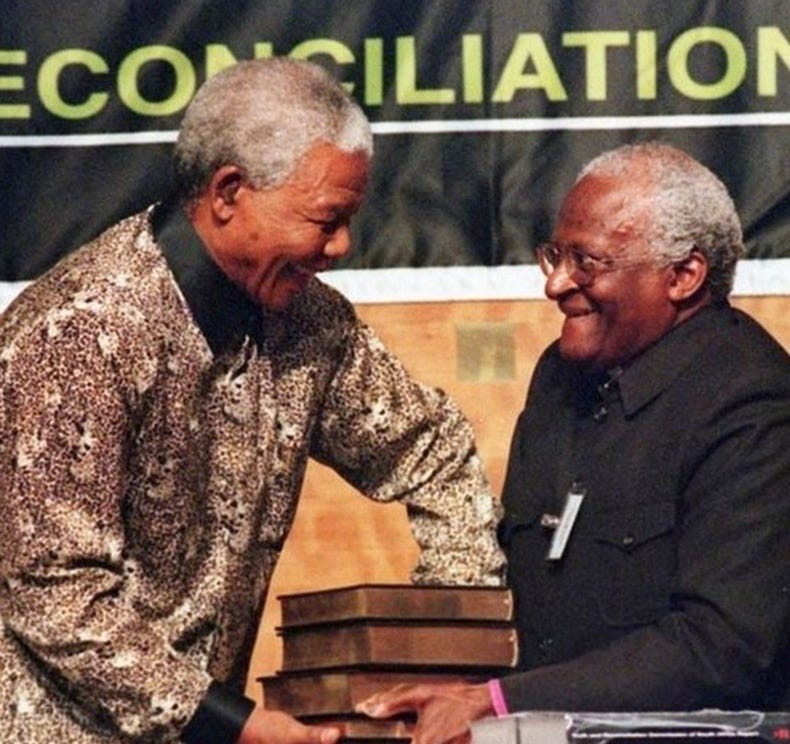

“He was first and foremost a priest, not a politician, but for the best part of half a century he was the face of reconciliation and South Africa’s moral compass.”1

Tutu was awarded his Nobel Prize in 1984 for decades of nonviolent but unyielding civil disobedience in the jaws of the brutal apartheid regime.

Later, at Nelson Mandela’s request, he became the architect and chair of the landmark Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which publicly laid bare in gruesome detail the racist horrors perpetuated under White colonial rule.

Yet somehow, despite decades of struggle against evils almost beyond comprehension, a common thread in the obituaries celebrating Tutu’s life was his unfailing playfulness, sense of humor, and yes, joyfulness.

As he himself said:

“We are meant to live with joy. Not that life will be easy or painless [but] we can turn our faces to the wind and accept that this is the storm we must pass through.

“Discovering more joy does not, I'm sorry to say, save us from the inevitability of hardship and heartbreak [but] we can face suffering in a way that ennobles rather than embitters. We have hardship without becoming hard. We have heartbreak without being broken.”

These words come from The Book of Joy,2 the fruit of five days of intensive private talks between Archbishop Tutu and his close friend Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, on the occasion of the latter’s 80th birthday in 2015.

Despite being frail, and already ailing, Tutu had traveled from South Africa to the Tibetan’s home-in-exile in Dharamsala, India for what would be their last time together.

Ironically, South Africa’s post-liberation government had refused the Dalai Lama permission to travel to Cape Town for Tutu’s own 80th birthday following vociferous complaints from China, South Africa’s chief trading partner (and the occupier of Tibet). The Archbishop was furious with his own government over this capitulation and let it be known in no uncertain terms.

This was neither the first nor the last time Tutu would berate the democratic regime he himself had helped bring to power. That same BBC tribute includes footage of an unforgettable tirade against corruption in the ruling African National Congress, delivered from the pulpit:

“I am warning you. I am warning you that we will pray, as we prayed for the downfall of the apartheid government, we will pray for the downfall of a government that misrepresents us.”

Obviously the Archbishop — who enjoyed being called Arch — had a very particular understanding of living joyfully.

It’s hard to do justice to The Book of Joy, whose 450 pages range widely across spirituality, psychology, ethics and politics, from the Christian, Buddhist and secular perspectives alike.

The book posits “Eight Pillars of Joy” as the essential foundation upon which a joyous life may be constructed, even and especially in the midst of hardship and struggle:

Perspective, humility, humor, acceptance3, forgiveness, gratitude, compassion and generosity

There is just one obstacle standing in the way. Oops: 14 obstacles:

Fear, stress and anxiety; frustration and anger4; sadness and grief; despair; loneliness; envy; suffering and adversity; illness and the fear of death.

Lord knows I’m no Desmond Tutu, nor I suspect are you. But neither are we facing invasion and imminent death. All of us here would certainly benefit from a little more time cultivating Column A and a lot less dwelling in Column B.

In that sprit, here, from 1969, are 33 minutes of direct connection to the root of joy. Simply lay down, close your eyes and turn it up loud. What can I say? It works for me.

“The Life and Legacy of Archbishop Desmond Tutu” https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-59793776. Three minutes long and well worth watching.

This link will take you to bookshop.org, a nonprofit Amazon alternative where you can order The Book of Joy (or any other book) with prompt free shipping and the proceeds sent to your favorite independent bookstore. I have it pre-set to Solid State Books in DC but you can plug in your own favorite.

Acceptance to Tutu “is the opposite of resignation and defeat.” It is simply the acknowledgment of what is. The Archbishop did not accept the inevitability of apartheid, for example, but he did accept its reality.

As Douglas Abrams, his longtime translator and co-author explains, Tutu carefully distinguished between righteous and destructive forms of anger. “He was not afraid of anger and righteous indignation in pursuit of peace, equality and justice in his homeland. It was a scythe of compassion, a chosen response rather than an uncontrollable reaction.”